A father shows his son the city in layers of memory, architecture and customs, in an intimate tour, where time is measured in almonds, kites and the persistent vocation of public spaces to summon and stay.

SANTO DOMINGO. – It's Sunday. Ringo and his father walked down from Villa Juana, heading for the Malecón. They walked steadily and without haste, before the cloudy afternoon faded and the city experienced the coolness of January. The boy was attentive to everything, as if it were the first time he had seen those streets, and his father walked with his memory alert.

Walking down Doctor Delgado Street, they passed the Steam House, supposedly undergoing renovations, though no one knew exactly what they were doing. The father pointed to the facade, and they peered through the construction fence, catching a glimpse of what remained of the ship's shape that had given the building its name. He sighed and said to Ringo, "People used to explore this city more slowly; they'd look around, stop..." The boy nodded, not quite understanding.

“Dad, but… how come this was a ship, a real ship?”

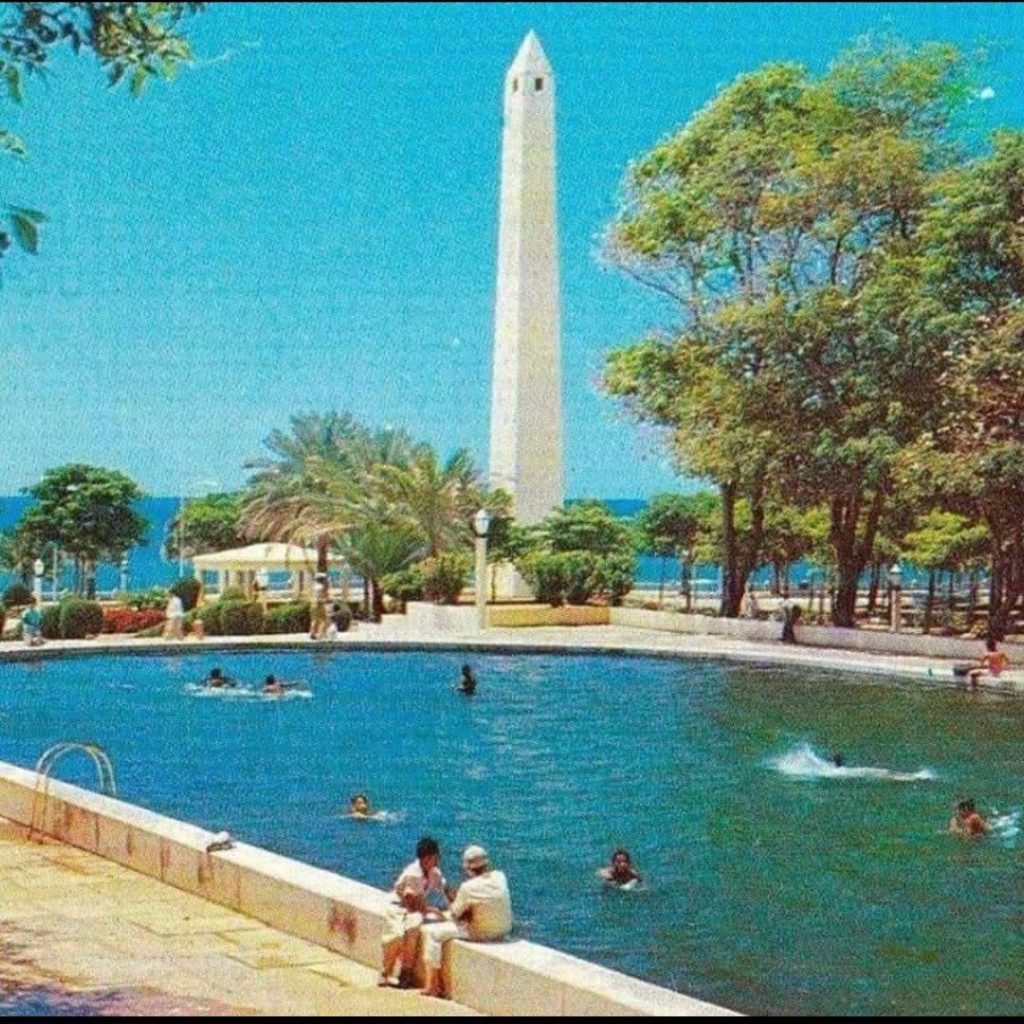

The park was designed by architect Guillermo González as a modern space for its time. (Photo/General Archive of the Nation).

“Let’s keep going, I’ll show you some pictures later. Let me show you where the president works,” and they continued walking until they stopped in front of the National Palace. “Look at it closely,” he told her. “That’s also part of the city and belongs to everyone, even though it looks far away.”.

They continued on. Ringo wanted to take a picture at the House of Roots and kept asking questions. The noise of the traffic faded away until the air began to change. The sea breeze slipped through the trees, and Eugenio María de Hostos Park appeared like an ancient clearing, full of long shadows.

To one side, several girls were exercising. They stretched their arms, lifted their legs, counted aloud. The park remained just that: an improvised gym, a public room, a place to be left without explanation.

Ringo picked up an almond from the ground. Then another, and more.

“Daddy, let’s go find a pebble,” he said, and darted off into the bushes in search of that polished stone. He found it, and they sat down under that enormous tree to crack almonds, slowly, carefully, listening to the dry thud of the stone against the fruit. Both at the same time, as if the gesture were inherited.

“When I was a boy,” the father began, “things weren’t like they are now, but they had already changed.”.

He paused and looked around. “When your grandfather used to come here, it was a different place, and he told me about it. He brought me here many times and, without knowing it, he saved me.”.

“But how can that be! This looks brand new.”.

José told him that the park was built in 1937 and was called Ramfis Park. He said it was designed by the architect Guillermo González as a modern space for its time. He explained that it had a swimming pool, wide paths lined with white lampposts, a seemingly endless staircase, and a direct connection to the sea, which could be seen from every side.

“My dad used to talk about this park as if it were a small city within the city. He said that here you learned how to spend the afternoon and be with others, how to share with others.”.

The old man had told him that there were, in addition to almond trees, oaks, many coral trees and even pine trees, as well as the elegant royal palms, of which there are no more.

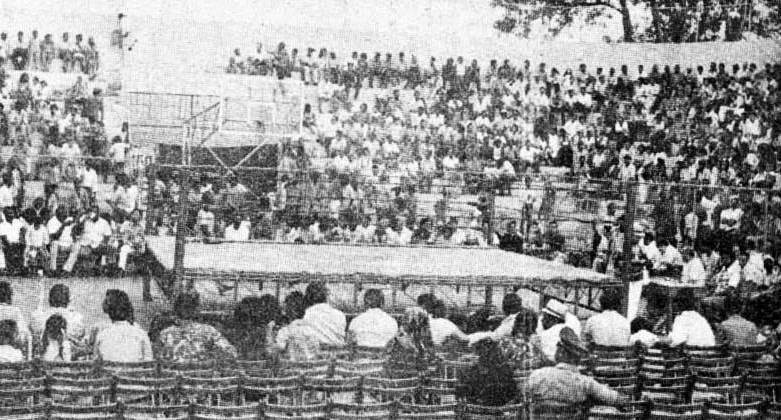

“When he used to bring me here, the fountain was gone, but people came from all the neighborhoods. Lovers came to eat chicken, and we came to make kites to fly across to the breakwater. When there was money, the biggest thrill was attending the wrestling tournaments: Jack Veneno’s technical stable against the rudos, which was Relámpago Hernández’s stable.”.

In the 1970s and 80s, Eugenio María de Hostos Park was the epicenter of Dominican wrestling. (Photo/Revista Ahora).

José's eyes squinted, as if he could clarify the hazy memories of his happy childhood with his father, in that same park that he was now showing to his son.

Ringo looked at him in surprise. His father described the ring, the people surrounding it, the posters plastered on posts and walls: thick paper, enormous red and black letters, exaggerated names, "Technicians vs. Rudos," "Mask vs. Hair." Matches advertised as if they were definitive, almost epic battles.

“We shouted without shame, and the best part was that we believed. Look, there’s the statue in honor of Jack Veneno. They should put one up of his mother, Doña Tatica, whom he loved so much.”.

Ringo listened in silence, watching the nine-foot-tall athletic figure who seemed to be shouting the cry of "Men up in the air, flying kicks!" It was as if he hadn't really left, he'd just learned to stay still.

At twelve years old, Ringo was inheriting a park that no longer existed completely, but that lived on in his father's voice and, before that, in his grandfather's.

“Let’s go there, to the corner, across from the Abreu Clinic,” José said, and they walked slowly along the sidewalk. It smelled of roasted peanuts. “I ate my first chimichurri here, and your grandfather used to stuff himself with frikitaki here. Let me take you to that corner store so you can have some chicharrón. That’s what we should do now.”.

The structure was built in 1937 and was called Ramfis Park. (Photo/General Archive of the Nation).

They both laughed, while the boy nodded and rubbed his hands together; he loved pork rinds.

“And what is a frikitaki?” he asked.

José explained that it was a kind of simple sandwich, made with water bread, salami, and tomato. “Old-fashioned street food, from when people walked the city. That was from your grandfather’s time. Before chimis.”.

In the times of the grandfather, the father, and the son, customs were different, and the music, food, and drinks were different. It was a different city, with a different kind of bustle, although Eugenio María de Hostos Park is still there, changing its design, but with the same vocation to bring people together.

Ringo thought that the city could also be judged by its food. They left the corner store. His father pointed north toward the New City Courthouse. “That’s where they bring the corruption defendants to court,” he said, and turned to walk toward the Malecón.

He told her about how the park changed its name and uses. How it lost some things, gained others, dimmed and brightened with the times. How, even so, it remained a place where one could stay without consuming anything, without having to leave quickly.

As the sun began to set, they crossed towards Plaza Juan Barón, skirting the obelisk. The sea breeze was stronger there. Several fishermen were killing time, waiting for fish to bite—they already knew the trick—while some girls tried to capture the fading sunset on their cell phones.

“We used to come here too,” said the father, “to fly kites and capuchin birds until the sun went down. The best time was Lent, with its warm breeze that quickly fills even the crates. We’ll come back during Holy Week.”.

They sat facing the sea. The sky turned reddish, thick, as only happens in the Caribbean winter. The sun slowly and quietly said goodbye.

Ringo gazed at the horizon. He thought of the almonds, the Callao, his grandfather's frikitaki, his father's chimis, those fights, the park that had been so many things and was still a place to stay.

He said nothing, but he knew that one day he would return. He wanted to go back to his old man, even if it was just to grind almonds, like you do with things you don't want to lose.